|

Euroasian Jewish News

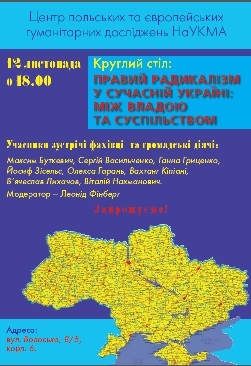

Panel discussion participants, left to right: Vyacheslav Likhachev, Anna Grytsenko, Leonid Finberg, Maxim Butkevich, Josef Zisels, Sergei Vasilchenko, Vitaliy Nahmanovich

|

Panel on Ukrainian Radical Right Movements Takes Place in Kyiv

14.11.2013 On November 12, 2013, the panel “The Radical Right in Contemporary Ukraine: Between the Government and Society” took place in Kyiv at the initiative of the Euro-Asian Jewish Congress (EAJC) General Council Chairman Josef Zisels. Among those who took part in this panel discussion were sociologists, political experts, and historians, which talked about Ukrainian national radicalism from different points of view. One thing, however, is doubtless: that in recent years it has been mostly associated with the All-Ukrainian “Svoboda” Union.

The reason for analyzing “Svoboda” particularly now is self-evident: it has now been a year since the elections after which a national-radical party achieved independent representation in the Ukrainian Parliament for the first time. In November 2012, many observers out forward theories, some of which completely contradicted others. According to some observers, after becoming a parliamentary party (as opposed to a “street” party), “Svoboda” would start to accept the rules of the political game and inevitably drift towards moderateness. Yet other believed that after receiving deputy mandates, the national-radicals would cast off their reserve even more and stop veiling their views, since xenophobic and extremist tendencies would be made legitimate by their presence in the Parliament. Now that a year has passed, an attempt seems to be in order to analyze the dynamics of “Svoboda’s” political evolution over the year that it has been in a new, parliamentary environment.

Additionally, there are reasons to believe that cooperation between the national-radical party and other political parties in the opposition will be actively used by the current government in political battle. The political technologies aimed at discrediting the opposition through affirmation of “Svoboda’s” extremism and xenophobia will involve provocative acts, up to but not limited by illegal activities, the blame for which will be placed squarely on “Svoboda’s” shoulders. These tendencies are especially worrying in light of the presidential elections coming up in 2015.

It is thus especially important to have professional discussions on “Svoboda’s” place in current political process, its current radicality, and how xenophobia features in its ideology and activities.

When opening the panel, Josef Zisels stressed how important it is to adequately understand where “Svoboda’s” xenophobic and anti-Semitic stances belong in a wider social and political context and pointed out how certain government bodies and persons affiliated with these bodies, including representatives of national minorities, make a conscious effort to hyperbolize them. The Chairman of the EAJC General Council provided data on anti-Semitism in Ukraine, both the dynamic of the last few years and in comparison to other European states. “We do not want to whitewash ‘Svoboda’ or deny the anti-Semitism of several of its leaders,” the speaker underscored, “we merely want for this phenomenon to be seen for what it is - no more, no less.”

Maxim Butkevich, coordinator of the “No Borders!” Project of the Center for Social Action noted that legitimating the presence of “Svoboda’s” position in the media legitimizes xenophobic discourse, which is currently racist, migrantophobic, and homophobic. The expert stressed that a certain illusion of Svoboda’s evolution to moderateness also means that acceptable xenophobia is also gaining ground in society. While national-radical ideas move more to the arbitrary social and political “center,” they at the same time become more of a factor in influencing said “center.”

Sociologist Anna Grytsenko read a report based on data collected by the Centre for Society Research, which held an all-Ukrainian monitoring of acts of protest. The report focused on the main directions of “Svoboda’s” activity in the streets in the post-election year. A comparison of this data in several key points with the average Ukrainian protest and access to general data on all radical right political forces provided the experts with rich material on “Svoboda” and its method.

Political studies scholar Alexei Garan’ repeated his conjecture that he had initially presented right after the parliamentary elections - he believes that “Svoboda” is currently at a crossroads and is right now once again open to evolving into either a moderate nationalist party or to preserving its radical ideology and rhethoric.

EAJC General Council member, leader of the program on monitoring and analyzing manifestations of xenophobia, Vyacheslav Likhachev dedicated his report to analyzing the provocative political technologies in inter-ethnic relations, used by experts in engineering social developments on behalf of the current government. According to the expert, the artifical dichotomy created through dirty PR tricks leads the electorate to make a choice in a false system of coordinates, thus choosing between “Nazis” and “bandits.” The implementation of this scenario, according to Likhachev, is a threat to national minorities, which the government attempts to attract to its side in this confrontation, thus creating an image of the opposition as a radical Ukrainian ethno-nationalistic force. At the same time, provocations in inter-ethnic relations are far from harmless, the expert says. “Paper monsters created by political technology and the cynical imagination of the provocators tend to become flesh and blood. In 2004, to create a scary image of Fascists supporting Yuschenko for the TV, the government’s political technologists had to pay people to wear a pretty uniform and lead them on a march through Kyiv’s Khreschatyk street, raising their right hands in a Nazi salute. But two years later, other youths bought cammo with their own money and went out into Kyiv’s center to perform the Nazi salute on their own and without any provocation. This was on October 14, 2006, the date of the first relatively large neo-Nazi rally.”

Sergei Vasilchenko noted in his speech that he believes “Svoboda” had attracted a significant amount of relatively moderate activists before the elections, who simply saw no other opportunity to realize their political ideas. Now that a year after the elections has passed, “Svoboda” may disappoint these temporary allies through its inaction or non-constructive activity and thus lose its moderate wing, evolving into an even more radical party against the expectations of more optimistic watchers.

The historian Vitaliy Nahmanovich talked about how the growth of both right and left-wing radicalism is not a problem in itself, but it is an important symptom of problems that do exhist in society, similar to how a fever is not an illness but the symptom of one. The historian believes that left-wing radicalism grows when there are unresolved social problems in a given society, while the growth of national radicalism is a symptom of problems in the national sphere.

After the panel’s speakers had been done with their reports, a lively discussion followed.

The discussion was moderated by EAJC GEneral Council Member, the Director of the National University “Kyiv-Mohyla Academy” (NaUKMA) Center for the Study of the History and Culture of East European Jews Leonid Finberg. The premises for the panel had been provided by the NaUKMA Center for Polish and European Studies.

|

|