|

World Jewish News

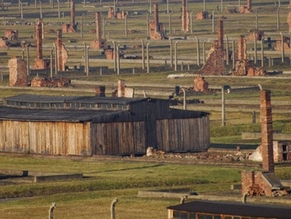

A section of barracks at the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum in Oswiecim, Poland. Photo by: AP

|

Poland demands return of Auschwitz barracks from U.S.

24.02.2012, Holocaust Polish and U.S. officials are engaged in intense talks to determine the fate of a sensitive object: a barrack that once housed doomed prisoners at the Nazis' Auschwitz death camp and is now on display at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Poland is demanding the return of the artifact, which has been on loan to the Washington museum for more than 20 years and is an important object in its permanent exhibition. But the U.S. museum is resisting the demand, saying the valuable object shouldn't be moved partly because it is too fragile.

"Due to the barrack's size and the complexity of its installation, removing and transporting it to Poland presents special difficulties, including potentially damaging the artifact," the U.S. Holocaust museum said in a statement to The Associated Press. "Both the Museum and our Polish partners have been actively discussing various proposals, and we remain committed to continue working with them to resolve this matter."

The issue has arisen because of a Polish law aimed at safeguarding a cultural heritage ravaged by past wars, particularly World War II. Under the law, passed in 2003, any historic object on loan abroad must return to Poland every five years for inspection. While Poland appears open to renewing the loan, it says the barracks must return — at least temporarily.

Because of the rule, the U.S. museum in recent years has already returned thousands of objects dating to the Holocaust, including suitcases, shoes and prosthetic limbs, often in exchange for new, temporary loans of similar or identical items.

The barracks on view in Washington are, in fact, just half of a wooden building where prisoners slept in cramped, filthy and often freezing conditions as they awaited extermination, often in gas chambers. The remaining half still stands at Birkenau, a part of the vast Auschwitz-Birkenau complex.

The two camps, Auschwitz and Birkenau, are about two miles (three kilometers) apart but were part of the same machinery of death during the war and the complex is typically referred to simply as "Auschwitz."

The director of the Auschwitz-Birkenau museum, Piotr Cywinski, accuses the U.S. institution of violating the terms of a 20-year loan on the barracks, saying the loan expired in 2009.

"We have indicated many times that this half of the barracks must return, that there is no other solution in accordance with the law," Cywinski said. "It's a very important object, not just for Washington but for the integrity of Birkenau, the last authentic site of Holocaust remembrance among all the major death camps."

Many of Poland's paintings, churches and other cultural gems were stolen, burned or otherwise destroyed during World War II, when Nazi Germany occupied the country, killed 6 million Polish citizens and built death camps across the country where they brought Jews and others from across Europe for extermination.

The legacy today is that the country possesses few old Polish treasures but has many Holocaust relics — including the sprawling site of Auschwitz-Birkenau in the south of the country that is one of the most visited Holocaust remembrance sites in Europe.

The memorial site, in fact, has many personal items that belonged to victims and frequently loans them out to institutions across the world, including Yad Vashem in Israel.

The matter between the Polish and U.S. institutions is extremely delicate and officials on both sides have resisted giving many details, or saying how the matter might be resolved. Poland's ministries of foreign affairs and culture are also involved in the matter but did not respond to AP requests for comment.

Although the problem might appear intractable, the U.S. Holocaust museum and the Auschwitz-Birkenau museum have cooperated well in the past and share similar missions of Holocaust remembrance — leading to expectations they will reach an eventual compromise.

The U.S. Holocaust museum confirms that the 20-year loan on the barracks began in 1989, but says that it was a renewable loan — and notes that Polish law was changed since then.

The fate of Cywinski, the Auschwitz museum director, is at stake in the matter. Under the law on protecting historic artifacts, he could be jailed for up to two years if he fails to obtain the return of any object on loan.

Roman Rewald, a Warsaw-based lawyer who has represented the U.S. Holocaust museum in the past on a pro-bono basis and has knowledge of the current discussions, says the matter comes down to Polish law, which is rigid and hard to work around.

The law would do a good job, for instance, of stopping an official from giving away a precious 16th century painting, but isn't as well-suited to regulating Holocaust artifacts, which probably shouldn't be moved so often.

"The Polish law is designed to make sure that nobody has any leeway in allowing Polish artifacts to leave the country permanently," Rewald said. "Poland is trying to protect its artifacts, all of them. Unfortunately Holocaust artifacts, which Poland has an abundance of, fall into the same category as all the other artifacts which Poland has been robbed of during wars, especially World War II."

Haaretz.com

|

|